Welcome to NHL99, The Athletics countdown of the top 100 players in modern NHL history. We rank 100 players but call it 99 because we all know who is No. 1 — it’s the 99 spots behind No. 99 we have to figure out. Every Monday to Saturday until February we will introduce new members to the list.

The disdain between the Avalanche and Red Wings wasn’t the first rivalry Joe Sakic found himself in. He began his NHL career in Quebec City with the Nordiques, the less successful team in the heated Battle of Quebec. Over an 11-year span, the Nordiques and Montreal Canadiens played each other five times in the playoffs, including once in Sakic’s playing career. A few years before Sakic entered the NHL, a postseason game between the two ended with 11 ejections. There was vitriol between the two clubs. Hatred.

And yet, when Sakic — the Nordiques’ last captain before their move to Colorado — was introduced at the 2022 NHL Draft in Montreal, he heard nothing but cheers. When he walked to the stage to accept the Jim Gregory Memorial General Manager of the Year Award, fans in red Canadiens jerseys rose to applaud. The sound in the Bell Center swelled as he began to speak.

That’s the reception you get as one of the most beloved figures in sports.

“Merci beaucoup,” he said, dusting off some of the French he learned while with the Nordiques.

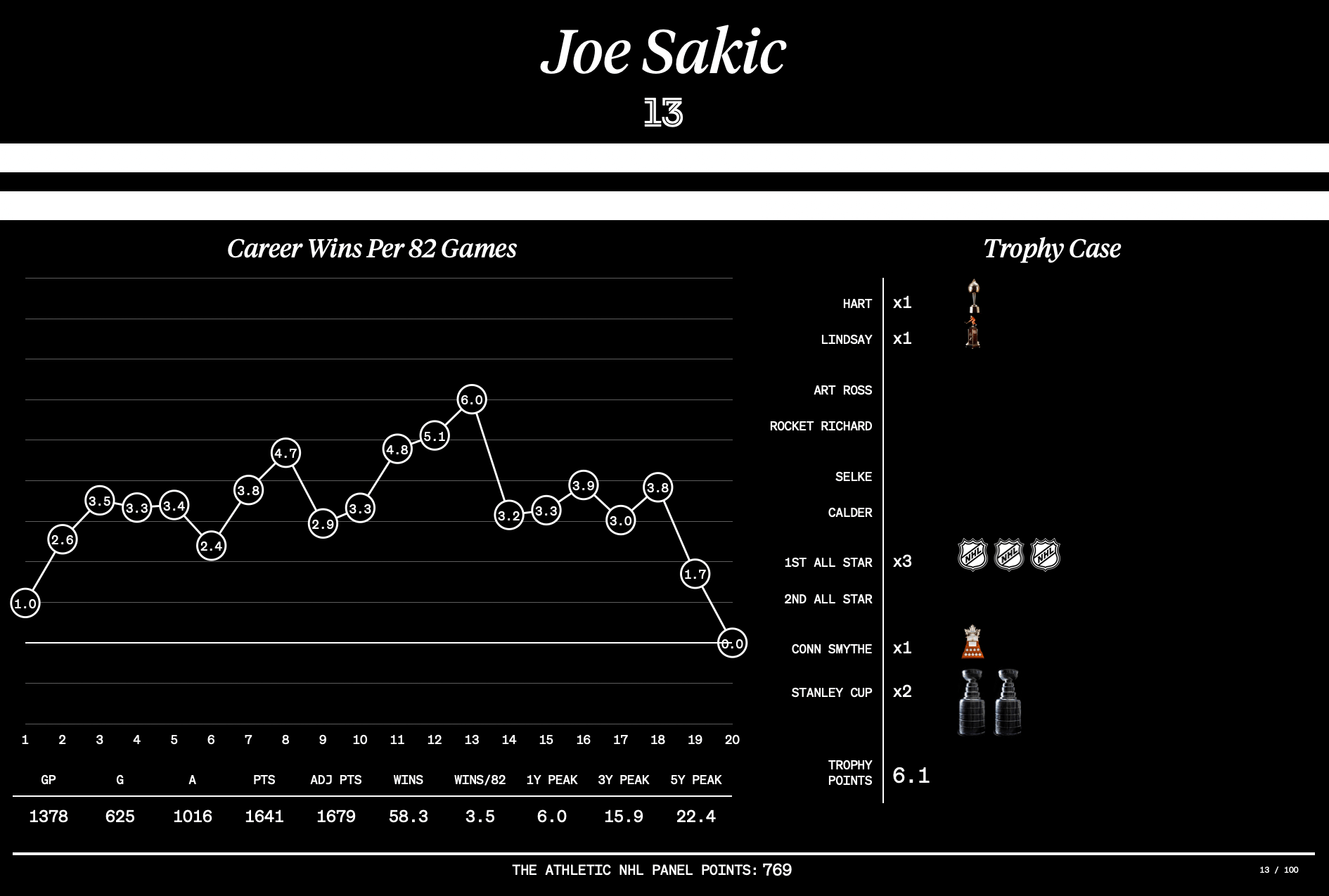

Not only is Sakic one of the best hockey players of all time, coming in at number 13 Athletic’s list of today’s best NHL players. He is also one of the most widely respected. Fans in Quebec City adore him nearly three decades after the Nordiques left town. Canadiens fans are still rooting for him. He even had the respect of the Red Wings. Mike Ricci, who played with Sakic in both Quebec City and Denver, recalls that Sakic and Detroit captain Steve Yzerman were “pretty much alone” during the rivalry. Even opponents held them in high esteem.

“You respect the king of the other team,” said Darren McCarty, who was with Detroit at the height of the rivalry. “We all loved Joe Sakic. We all thought he was great.”

“The rest of us loved to hate,” adds Ricci.

And of course, there are the people in Denver, where Sakic has a great reputation. He won the Conn Smythe Trophy for playoff MVP in 1996, the team’s first year in Colorado. He led the team to a pair of Stanley Cup wins, won a Hart Trophy, a Lady Byng Trophy and finished his career with 1,641 points. His success—combined with his team’s—helped the fan base take off. Then, 13 years after his playing career ended, he led the Avalanche to another Stanley Cup as the team’s general manager.

He is the face of the sport in Colorado, and has been since the team arrived. He ushered in a new era of professional sports.

“Obviously, John Elway was the guy in Denver at the time and will always be the guy in Denver. I know that,” said broadcaster John Kelly, who called Avalanche games after the team’s move. “But Joe Sakic, from Day 1, really ( been) the hockey guy in Denver.”

At first, Ricci wrote off the rumours. He didn’t think the Nordiques would actually move. But as the 1994-95 season progressed, the talks began to feel more serious. The team had problems financially, but not for lack of support from the fans.

“Marcel Aubut, the owner, had dinner with us,” says Ricci. “You could tell, the way he talked, it was terrible.”

The talk turned out to be true. Aubut sold the team to COMSAT Entertainment Group, which also owned the Denver Nuggets. COMSAT moved the team to Denver.

“It was kind of a worrying time but an exciting time,” says Curtis Leschyshyn.

They would be leaving a city with a solid, large fan base and heading to a place most players didn’t know much about. How would they fit into a market with three other major professional sports teams, where the NFL’s Denver Broncos were the kings? There was a passionate fan base there, but the players didn’t know it at the time.

At the time of the move, Sakic was the face of the Nordiques. First, his performance was exceptional, even when the team was struggling. He had three 100-plus point seasons in Quebec City, two of which came when the Nordiques won 12 and 16 games. Fans in Quebec are knowledgeable about hockey and know how to recognize talent, notes Leschyshyn. Sakic clearly had it.

And so was the way he carried himself.

“A captain all the way,” said Quebec City resident Christian Robitaille, who grew up with the Nordiques.

“He was always respectful to the Nordiques fans,” adds Ricci. “He loved being there. He loved the fans there. There was never a hint that he wanted out, even when they were bad. He went through it, went through the bad and made it what it is today.”

Towards the end of the team’s days in Quebec City, the roster began to come together. Sakic was a star, and the Eric Lindros trade gave the Nordiques a bevy of pieces, including Peter Forsberg, who won the Calder Trophy in 1994-95. The Nordiques had persevered through their terrible seasons and made the playoffs in 1995, only to lose in the first round to the New York Rangers.

“That’s what we did in Quebec: We learned how to lose and eventually we learned what it takes to win,” says Leschyshyn.

Unfortunately for Nordiques fans, they never got to see those lessons come to fruition. Sakic and the Nordiques went to Denver, ready to take the next step as Stanley Cup contenders.

Want to know how to win over a new fan base? Start by winning games.

The Avalanche did just that in their first season. This wasn’t an expansion team without top talent. This was a club with star power, a proven captain in Sakic and, thanks to a midseason blockbuster, a Hall of Fame goaltender in Patrick Roy. They were, as longtime employee Jean Martineau says, ready to explode.

The Avalanche were young and dynamic – which Martineau, who handled the team’s communications in both Quebec City and Colorado, felt matched Denver’s energy in the mid-1990s. And although the Avalanche was new, the city already had hockey fans. The University of Denver is a traditional NCAA power, and the city had an NHL team from 1976 to 1982, when the Colorado Rockies moved to New Jersey and became the Devils.

The existing fans watched an entire show in the first season. Thanks in large part to Sakic’s quick, powerful shooting and career-high 120-point season, the Avalanche finished the regular season with the league’s second-best record. That led to the scene where Sakic became a household name around town: the playoffs.

“Without the real hockey fans, the market really started to embrace the team during the Stanley Cup run,” said Martineau, now a travel and communications consultant.

Joe Sakic accepts the Stanley Cup from Gary Bettman in 1996. (B Bennett/Getty Images)

The run could have been much shorter if the second round had gone a little differently. In the second round, Colorado trailed 2-1 in the series and was locked in a triple-overtime Game 4. Early in the third overtime, Ricci found himself on the ice with Sakic. He says he often played with more skilled players as the matches got longer. The fast players slowed down, but he joked that he could maintain the same not-too-fast speed for 20 periods if needed. And when he was on the ice in those moments, all he wanted to do was get Sakic the puck.

Ricci got the puck in the offensive zone and then moved it along the boards to Alexei Gusarov. Sakic, meanwhile, cut toward the net, where Gusarov beat him with a tape-to-tape pass. The captain redirected the feed into the net and threw his arms over his head in excitement.

“That was the biggest goal of the playoffs for me,” said Kelly, who adds that it was perhaps the most memorable game he’s broadcast because of all the pressure on Colorado.

“We really didn’t want to go down 3-1,” Sakic said on TSN after the game.

Colorado won the next two games, including a double-overtime Game 6. Sakic didn’t win the game that night, but he did get a secondary assist on Sandis Ozolinsh’s overtime tally. The Chicago series, which went four games into overtime, was when Martineau saw the buzz around Denver extend beyond die-hard fans.

“You come in and you win like that, and the first year people were drawn to it,” says former defenseman Adam Foote.

Sakic’s heroics continued. In the conference finals against Detroit, he scored twice in the decisive Game 6, including the go-ahead goal in the second period. Then he led Colorado to a sweep of the Panthers in the Stanley Cup Finals. After Game 4, NHL commissioner Gary Bettman called him over to accept the Conn Smythe Trophy for playoff MVP. He averaged nearly a goal per game in the playoffs (18 of 22) and set a since-broken record with six game-winning goals.

“He knew how good he was,” Ricci says. “He just didn’t feel the need to tell anyone or talk about it.”

He didn’t need to get accolades with the Avalanche. Largely because of his heroics, Denver had its first professional championship in any sport. He lifted the Stanley Cup above his head, his mouth open in a wide smile.

Sakic’s brilliance continued. He led the Avalanche to another Stanley Cup in 2001 and never left the Nordiques/Avalanche franchise. The team retired his number and he entered the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2012.

“He’s been blessed with a lot of natural talent,” Leschyshyn says. “But he’s also worked hard at his craft and become very successful. Not by accident or dumb luck. He’s earned every accolade he’s ever achieved.”

During Sakic’s peak, kids mimicked his game across Colorado. Anaheim Ducks standout Troy Terry, who grew up in Denver, wears No. 19 because of the Avalanche greats. He also remained a fan favorite in Quebec, even after the Nordiques moved. Current NHLers Patrice Bergeron and Jonathan Marchessault, who were originally Nordiques fans, kept up with their favorite players — including Sakic — after the team moved.

During the Denver portion of his career, Sakic maintained the reputation he built in Quebec City. He was not brash or arrogant; he was simply a world-class athlete with his head in the right place.

“I always say if people didn’t know anything about hockey and went up to talk to him, you’d never know he was a Hall of Famer with three Stanley Cup rings and (an) Olympic medal,” Leschyshyn said. “He didn’t come across that way.”

But he got those accolades too. He’s still the face of hockey in Colorado, and that won’t change anytime soon.

“He’s in the rafters, man,” Foote says. – Everything speaks for itself.

(Top image: Elsa/Getty Images)

#NHL99 #Joe #Sakic #remains #King #Denver #Quebec #City #NHL #map