Bear with me: this is, on the face of it, a strange idea. But is it possible that Apple manufactures its Mac computers for powerful?

Okay, okay, I know: how can having a computer that’s too powerful be a bad thing? But after this week’s announcement of the new MacBook Pro and Mac mini, I found myself wondering if the company has painted itself into a corner, vis-à-vis its impressive hardware.

Admittedly, it’s a strange state of affairs when you find yourself wondering if maybe Apple has gotten too good at making computers so powerful that they’re overkill for most tasks, but you don’t have to look too far to see otherwise example of the same phenomenon.

This is a battle that Apple has long wrestled with on the iPad. Ask any user who pushes the case on an iPad Pro and the consensus is likely to be that the hardware is amazing and incredibly powerful – if only the software could keep up.

Foundry

To be fair, the problem with the iPad is more about what’s available on the platform. Yes, you can have all the power of an M2 processor, but how do you actually use it? Most iPad users don’t do video editing, high-level coding, or work with giant Photoshop images. (That said, Apple’s advertising would like to remind us that any of us could do all of these things … if only we’d buy an iPad Pro.)

I don’t mean that the lack of powerful software is what lasts Mac back: If anything, Apple is clearly committed to letting users throw as much horsepower at pro-level applications as they possibly can. And it does so by offering lots of different machines powered by a variety of increasingly powerful chips. When Apple announced its first post-M1 processors in recent years, the rollout assumed almost comical self-topping proportions as it first announced the M1 Pro and M1 Max, and then in 2022, the M1 Ultra. It felt a bit like one of those old infomercials “But wait! There’s more!”

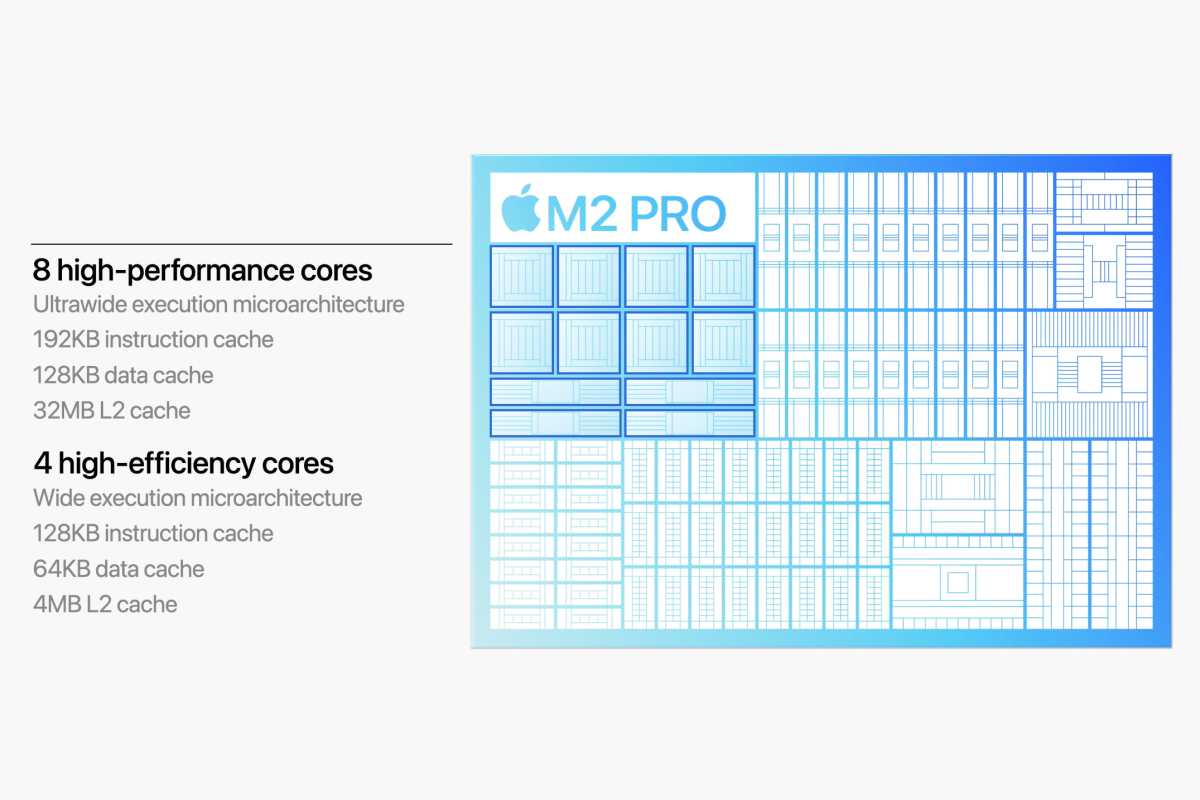

The truth is that even the Pro series processors are overpowered for most common computing tasks. E-mail, web browsing, word processing, spreadsheets – the M1 and M2 handle it all with power to spare. Still, Apple continues to squeeze out faster and faster chips, appeasing a smaller and smaller niche in the market (albeit a high-margin one). Between the M2 Pro and M2 Max MacBooks, M2 Pro Mac mini, Mac Studio and the still-to-be-announced Mac Pro, it seems there are more machines aimed at the high-powered professional desktop market than consumers. and yet, the higher you go, the thinner the air becomes: there are fewer people in the market for such powerful machines.

The long-standing paradigm of the computer industry is that the more you spend, the more power you get. It used to be embodied by a single spec: the clock speed of a processor. by the late 1990s and early 2000s, customers had fixated on clock speed as the only measurement that mattered—an idea that Apple even tried to dispel with its idea of the “megahertz myth.” And to some extent it worked: Search Apple’s specs or press releases for its new Macs, and you won’t even see the speed of any of its processors.

It’s all about core count now, and we’ve moved past clock speed.

Apple

Instead, it has been replaced by an alternative metric: cores, both CPU and GPU. The more money you spend, the higher the number of parallel processing units. But even with that, we’ve fallen back into the trap of just happily increasing numbers, focusing on “bigger is better.” And as with the megahertz myth, the fixation on cores ignores the features that really make the difference between models for most users.

Because when all your devices are ridiculously powerful, the difference comes down to other more tangible features: Screen size. Form factor. Number and type of ports. Heck, port placement. All of these are easier to understand by (and probably more relevant to) the market than abstract numbers like “20 percent faster.” Sure, for a visual artist pumping out renders that eat up their entire CPU, 20 percent faster could mean saving them a day’s worth of work. But no one thinks that a 20 percent faster CPU will let them answer email so much more efficiently that they can start the weekend on Thursday. It is simply not the limiting factor.

With the first two generations of its own chips under its belt, Apple has easily proven that it can make hardware that is second to none. And I’m certainly not advocating that Apple not try to produce the best chips it can. But no jump in the near future will be as big as the first, from Intel to Apple silicon, and as it nears the end of this transition period, Apple may want to consider other ways to push the Mac forward — new form factors? touch screens? – rather than just increasingly faster chips with more cores. In other words, to throw some of the company’s most famous words back in its face, maybe it’s time to think differently again.

#power #Apples #silicon #holding #Mac